Managing to Build Bridges - Part 5: Poetry Has No Rules

Nani has a gift for entering others’ cultures in a respectful and sensitive way. That gift, combined with her strong curiosity and sense of adventure, has led to a unique trajectory from her childhood in Indonesia to her current job as a project manager at LinkedIn. In Part 5 she describes her discovery of poetry.

Sarah: I think you started studying poetry writing with me right after you began working full-time at the Language Acquisition Center.

Nani: That’s right, we met in the fall of 2002.

Sarah: What drew you to poetry?

Nani: I’d read Charles Bukowski in one of my undergrad classes. Back home in Indonesia, poetry had all kinds of rules. When I read Bukowski, I was surprised and impressed that poetry could look and sound like that. “Wow, you can include cuss words and write in free verse about daily stuff!” I saw a flyer in the campus library about your poetry workshops and consultations. I was curious. When I first started working with you, if you remember, I didn’t join a workshop—I was too shy. You had put on your flyer that you also worked with people one-on-one, and that appealed to me. Then after you told me more about your workshops, I realized it would feel safe—I didn’t have to be somebody already in order to join.

Looking back, I can see that being in the workshop was such good practice in terms of learning how to express myself in a more public forum. I also paid attention to how you taught the class. All the students were working in different styles, writing different kinds of work. The course readers you put together introduced me to a lot of different kinds of poetry as well. I remember you had us read a poem about Frida Kahlo and you pulled a biography of her off your shelf; it had lots of reproductions of her work. You introduced me to Joanne Kyger’s work too. I was attracted to it for the same reasons I was drawn to Bukowski—the frankness, the dailiness, no rules. I wanted to write like that.

My undergraduate studies in English literature and Language Studies were more externally oriented. That’s where I first realized that people can express their individual visions and others might read that work. Coming from my culture, that was such new, exciting idea. Then in your workshops I was looking internally at what I had to say. The two approaches went hand in hand.

Sarah: Tell me about becoming friends with Joanne Kyger.

Nani: After you introduced me to her work, I decided to attend Naropa’s summer writing program, which she taught in. A lot of students wanted to hang out with her but it seemed like they were mostly curious about her personal life and her marriage early on to Gary Snyder. I didn’t feel the need to ask about those things. She told me that she really appreciated that I just wanted to talk about her work. For a while after Naropa we wrote postcards to each other. Then she gave me her email address, and then she invited me to her home in Bolinas. From then on, I visited her about once a year.

I felt our deepest connection came mostly in relation to poetry—I appreciated her work, and she appreciated mine. In person, we were very fond of each other, but I now wish we had a deeper in-person connection. At one point she invited me to stay overnight at her place and I didn’t do it. I feel a little regretful knowing that I could have formed a deeper friendship and mentorship. She was very encouraging about my work. She published one of my poems in a local Bolinas newsletter.

Next: Human Remains and Cultural Artifacts

-

August 2021

- Aug 31, 2021 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 9: The Teacher Role Isn't My Essence Aug 31, 2021

-

June 2021

- Jun 13, 2021 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 8: Machines Spilling Out Teachers Jun 13, 2021

-

April 2021

- Apr 14, 2021 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 7: A Waterfall of Inspiration Apr 14, 2021

-

February 2021

- Feb 14, 2021 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 6: Grab the Right Computer File Feb 14, 2021

-

December 2020

- Dec 26, 2020 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 5: Yoga Is My Second Child Dec 26, 2020

-

November 2020

- Nov 5, 2020 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 4: Wow, This Is Me Nov 5, 2020

-

October 2020

- Oct 4, 2020 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 3: In Exile in My Own Country Oct 4, 2020

-

August 2020

- Aug 23, 2020 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 2: Openness to the Unseen Aug 23, 2020

- Aug 2, 2020 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 1: Let's Move Around; We'll Feel Better Aug 2, 2020

-

July 2020

- Jul 25, 2020 Educator Wellness Series Conclusion: Moving Forward with Wellness Jul 25, 2020

- Jul 6, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #10: Inhabiting the Dignified Stance of "Adequate" Jul 6, 2020

-

June 2020

- Jun 17, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #9: Jun 17, 2020

- Jun 3, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #8: Reducing Stress Through Body Scanning Jun 3, 2020

-

May 2020

- May 21, 2020 Facebook Live Event: A Conversation About the Impact of Saying Goodbye to Students May 21, 2020

- May 13, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #7: Setting Intention and Letting Go of Results May 13, 2020

- May 6, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #6: Practicing Goodwill as Self-Care May 6, 2020

-

April 2020

- Apr 29, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #5: Dealing with Constant Change Apr 29, 2020

- Apr 22, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #4: Listening to Silence Apr 22, 2020

- Apr 21, 2020 Facebook Live Event: A Conversation About the Importance of Self-Care Apr 21, 2020

- Apr 15, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #3: Apr 15, 2020

- Apr 8, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #2: Engaging Wisely with News and Media Apr 8, 2020

- Apr 1, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #1: Breathe ... Keep Breathing Apr 1, 2020

-

March 2020

- Mar 25, 2020 Educator Wellness Series for Collaborative Classroom Mar 25, 2020

-

May 2019

- May 19, 2019 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 8: Do We Want to Be Right in a Dictionary Sense? May 19, 2019

-

April 2019

- Apr 27, 2019 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 7: You Just Need to Find a Good Husband Apr 27, 2019

- Apr 6, 2019 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 6: Human Remains and Cultural Artifacts Apr 6, 2019

-

March 2019

- Mar 17, 2019 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 5: Poetry Has No Rules Mar 17, 2019

- Mar 3, 2019 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 4: Dessert Goes to a Different Stomach Mar 3, 2019

-

January 2019

- Jan 13, 2019 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 3: I Felt Pretty Stupid Jan 13, 2019

-

December 2018

- Dec 9, 2018 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 2: Such a Bad Kid Dec 9, 2018

-

November 2018

- Nov 23, 2018 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 1: The Pressure to Be a Certain Type of Girl Nov 23, 2018

-

October 2018

- Oct 23, 2018 Leadership Without Ego - Part 6: Mayberry with an Edge Oct 23, 2018

- Oct 1, 2018 Leadership Without Ego - Part 5: Everyone Everywhere Deserves to Make Art Oct 1, 2018

-

September 2018

- Sep 10, 2018 Leadership Without Ego - Part 4: I'm About Ready to Swear Sep 10, 2018

-

August 2018

- Aug 19, 2018 Leadership Without Ego - Part 3: The Dalai Lama Breaks All the Rules Aug 19, 2018

-

July 2018

- Jul 29, 2018 Leadership Without Ego - Part 2: The Kids Melted Under That Praise Jul 29, 2018

- Jul 10, 2018 Leadership Without Ego - Part 1: The Workshop Was Neutral Territory Jul 10, 2018

-

May 2018

- May 26, 2018 The Alchemy of Service - Part 5: Watch Out, Someone's Behind You May 26, 2018

- May 6, 2018 The Alchemy of Service - Part 4: Fireworks and Tears May 6, 2018

- May 5, 2018 The Alchemy of Service - Part 3: Joann Wong! You Are Chinese! May 5, 2018

-

April 2018

- Apr 6, 2018 The Alchemy of Service - Part 2: Mom, It's Only a Nickel Apr 6, 2018

-

March 2018

- Mar 19, 2018 The Alchemy of Service - Part 1: Mouse Soup Mar 19, 2018

-

February 2018

- Feb 18, 2018 Back to the Garden - Part 4: Mountain Lion Footprints on the Deck Feb 18, 2018

- Feb 3, 2018 Back to the Garden - Part 3: "You're a Good Egg—Happy Easter" Feb 3, 2018

-

January 2018

- Jan 15, 2018 Back to the Garden - Part 2: "A Pretty Big Failure" Jan 15, 2018

- Jan 1, 2018 Back to the Garden - Part 1: "Aesthetic Shock" Jan 1, 2018

-

August 2017

- Aug 15, 2017 Goodbye Self-esteem, Hello Self-compassion – Part 3: Real Love Aug 15, 2017

-

July 2017

- Jul 31, 2017 Goodbye Self-esteem, Hello Self-compassion – Part 2: Mirror, Mirror Jul 31, 2017

- Jul 17, 2017 Goodbye Self-esteem, Hello Self-compassion – Part 1: Bashing Vasco Jul 17, 2017

-

May 2017

- May 28, 2017 This Thing I Found: Teens Teach Us How to See Freshly May 28, 2017

-

March 2017

- Mar 20, 2017 Dream On - Part 6: Dream Analysis Example Mar 20, 2017

- Mar 7, 2017 Dream On - Part 5: A Dream Analysis Technique (cont.) Mar 7, 2017

-

February 2017

- Feb 20, 2017 Dream On - Part 4: A Dream Analysis Technique Feb 20, 2017

-

January 2017

- Jan 22, 2017 Dream On - Part 3: Recording Dreams Jan 22, 2017

- Jan 15, 2017 Dream On - Part 2: Dream Recall Jan 15, 2017

-

December 2016

- Dec 30, 2016 Dream On – Part 1 Dec 30, 2016

- Dec 12, 2016 Enjoying the Ride of Serendipity Dec 12, 2016

- Dec 6, 2016 Agnes Martin: A Singular Career Dec 6, 2016

Back to the Garden - Part 4: Mountain Lion Footprints on the Deck

This is the last in a four-part series of posts based on an interview I conducted with the poet Hazel White, about the twenty-year process of writing her book Vigilance Is No Orchard, forthcoming from Nightboat Books. Scroll down for Parts 1–3.

Eighteen Years of Defeat Is a Strange Space

[When we left off with Hazel's story in Part 3 below, she had revised her manuscript yet again and sent it—yet again—to Stephen Motika at Nightboat.] He wrote back after some time. He didn’t like the changes. But he didn’t out-and-out reject the work.

Six months went by. One day I pulled out the manuscript again. I cut a third of the quotes and embedded the remainder more carefully in the manuscript. I sent it back to Stephen and wrote something like, “I’m not certain that I’ve fixed anything. If you could let me know your decision by Sunday I’d appreciate it. If the answer is no, I completely understand.” I almost wanted a rejection. There were many times during the whole process when I wondered if I were mentally ill. Eighteen years of defeat is a strange space.

Stephen wrote back and said he loved the rewrite. He had a lot of praise for it. But he also didn’t come right out and say he’d publish it.

I went to Brooklyn in the fall of 2016 and met him for breakfast. I was grateful that he had spent so much time on my manuscript and I was also nervous he might still be thinking it wasn’t done yet. I said hesitantly, Stephen, is it yes or no? He said, Yes. He said, Sorry, in my feedback I’ve been harsh on you. I said, That’s true. We laughed. He knows a lot about landscape architecture and admires Isabelle’s work, so he cared about this book. I’m of course very grateful now.

Mountain Lion Footprints on the Deck

I’ve thought a lot about why this project took twenty years. I’ve come to understand that as an English person, I wasn’t writing about a Southern California landscape from the perspective of someone raised here. I had to take up habitation in a foreign aesthetic. It’s very hard to have lost one’s original place. It’s even harder to write about that. Yet I felt I might never encounter a more mysterious or necessary subject. So what choice did I have? I had to address that desperate resettling.

I also think I was jealous of Isabelle’s power as an exquisitely intuitive maker. I wanted to write as powerfully as she created gardens. The project became finish-able when I realized I would always fail to fully get the experience on the page; that instead, I needed to allow the failure to enter the work, become part of it.

A third challenge to completing the work was my guilt that I was making an experimental poetry book, not the gloriously successful coffee table book Isabelle and I had originally envisioned.

But about six years ago I realized Isabelle wasn’t holding a grudge. Around that time she arranged for me to stay in the guest house at the garden she had created for Lillian Lovelace. The Lovelace garden features a pool with boulders in it, set under oaks, with a teahouse at its edge. It’s that placement of the human-made lines and the wild lines I described earlier, that reduces me to a noodle. I stayed in the teahouse for three days and nights. I swam in the ocean and in mountain creeks. I slept with the door open and in the mornings there were mountain-lion footprints on the deck. I wrote several poems.

Isabelle always knew I was more of a writer than I knew. She told me early on to stop calling myself a garden writer. She said I was an artist and a real thinker. By the time the book was finished, she had come to see me as being more true to myself as an artist than perhaps she’d been to her artist self during that time. So in the end, she’s glad it ended up how it did.

And so am I.

-

August 2021

- Aug 31, 2021 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 9: The Teacher Role Isn't My Essence Aug 31, 2021

-

June 2021

- Jun 13, 2021 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 8: Machines Spilling Out Teachers Jun 13, 2021

-

April 2021

- Apr 14, 2021 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 7: A Waterfall of Inspiration Apr 14, 2021

-

February 2021

- Feb 14, 2021 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 6: Grab the Right Computer File Feb 14, 2021

-

December 2020

- Dec 26, 2020 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 5: Yoga Is My Second Child Dec 26, 2020

-

November 2020

- Nov 5, 2020 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 4: Wow, This Is Me Nov 5, 2020

-

October 2020

- Oct 4, 2020 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 3: In Exile in My Own Country Oct 4, 2020

-

August 2020

- Aug 23, 2020 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 2: Openness to the Unseen Aug 23, 2020

- Aug 2, 2020 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 1: Let's Move Around; We'll Feel Better Aug 2, 2020

-

July 2020

- Jul 25, 2020 Educator Wellness Series Conclusion: Moving Forward with Wellness Jul 25, 2020

- Jul 6, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #10: Inhabiting the Dignified Stance of "Adequate" Jul 6, 2020

-

June 2020

- Jun 17, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #9: Jun 17, 2020

- Jun 3, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #8: Reducing Stress Through Body Scanning Jun 3, 2020

-

May 2020

- May 21, 2020 Facebook Live Event: A Conversation About the Impact of Saying Goodbye to Students May 21, 2020

- May 13, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #7: Setting Intention and Letting Go of Results May 13, 2020

- May 6, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #6: Practicing Goodwill as Self-Care May 6, 2020

-

April 2020

- Apr 29, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #5: Dealing with Constant Change Apr 29, 2020

- Apr 22, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #4: Listening to Silence Apr 22, 2020

- Apr 21, 2020 Facebook Live Event: A Conversation About the Importance of Self-Care Apr 21, 2020

- Apr 15, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #3: Apr 15, 2020

- Apr 8, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #2: Engaging Wisely with News and Media Apr 8, 2020

- Apr 1, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #1: Breathe ... Keep Breathing Apr 1, 2020

-

March 2020

- Mar 25, 2020 Educator Wellness Series for Collaborative Classroom Mar 25, 2020

-

May 2019

- May 19, 2019 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 8: Do We Want to Be Right in a Dictionary Sense? May 19, 2019

-

April 2019

- Apr 27, 2019 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 7: You Just Need to Find a Good Husband Apr 27, 2019

- Apr 6, 2019 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 6: Human Remains and Cultural Artifacts Apr 6, 2019

-

March 2019

- Mar 17, 2019 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 5: Poetry Has No Rules Mar 17, 2019

- Mar 3, 2019 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 4: Dessert Goes to a Different Stomach Mar 3, 2019

-

January 2019

- Jan 13, 2019 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 3: I Felt Pretty Stupid Jan 13, 2019

-

December 2018

- Dec 9, 2018 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 2: Such a Bad Kid Dec 9, 2018

-

November 2018

- Nov 23, 2018 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 1: The Pressure to Be a Certain Type of Girl Nov 23, 2018

-

October 2018

- Oct 23, 2018 Leadership Without Ego - Part 6: Mayberry with an Edge Oct 23, 2018

- Oct 1, 2018 Leadership Without Ego - Part 5: Everyone Everywhere Deserves to Make Art Oct 1, 2018

-

September 2018

- Sep 10, 2018 Leadership Without Ego - Part 4: I'm About Ready to Swear Sep 10, 2018

-

August 2018

- Aug 19, 2018 Leadership Without Ego - Part 3: The Dalai Lama Breaks All the Rules Aug 19, 2018

-

July 2018

- Jul 29, 2018 Leadership Without Ego - Part 2: The Kids Melted Under That Praise Jul 29, 2018

- Jul 10, 2018 Leadership Without Ego - Part 1: The Workshop Was Neutral Territory Jul 10, 2018

-

May 2018

- May 26, 2018 The Alchemy of Service - Part 5: Watch Out, Someone's Behind You May 26, 2018

- May 6, 2018 The Alchemy of Service - Part 4: Fireworks and Tears May 6, 2018

- May 5, 2018 The Alchemy of Service - Part 3: Joann Wong! You Are Chinese! May 5, 2018

-

April 2018

- Apr 6, 2018 The Alchemy of Service - Part 2: Mom, It's Only a Nickel Apr 6, 2018

-

March 2018

- Mar 19, 2018 The Alchemy of Service - Part 1: Mouse Soup Mar 19, 2018

-

February 2018

- Feb 18, 2018 Back to the Garden - Part 4: Mountain Lion Footprints on the Deck Feb 18, 2018

- Feb 3, 2018 Back to the Garden - Part 3: "You're a Good Egg—Happy Easter" Feb 3, 2018

-

January 2018

- Jan 15, 2018 Back to the Garden - Part 2: "A Pretty Big Failure" Jan 15, 2018

- Jan 1, 2018 Back to the Garden - Part 1: "Aesthetic Shock" Jan 1, 2018

-

August 2017

- Aug 15, 2017 Goodbye Self-esteem, Hello Self-compassion – Part 3: Real Love Aug 15, 2017

-

July 2017

- Jul 31, 2017 Goodbye Self-esteem, Hello Self-compassion – Part 2: Mirror, Mirror Jul 31, 2017

- Jul 17, 2017 Goodbye Self-esteem, Hello Self-compassion – Part 1: Bashing Vasco Jul 17, 2017

-

May 2017

- May 28, 2017 This Thing I Found: Teens Teach Us How to See Freshly May 28, 2017

-

March 2017

- Mar 20, 2017 Dream On - Part 6: Dream Analysis Example Mar 20, 2017

- Mar 7, 2017 Dream On - Part 5: A Dream Analysis Technique (cont.) Mar 7, 2017

-

February 2017

- Feb 20, 2017 Dream On - Part 4: A Dream Analysis Technique Feb 20, 2017

-

January 2017

- Jan 22, 2017 Dream On - Part 3: Recording Dreams Jan 22, 2017

- Jan 15, 2017 Dream On - Part 2: Dream Recall Jan 15, 2017

-

December 2016

- Dec 30, 2016 Dream On – Part 1 Dec 30, 2016

- Dec 12, 2016 Enjoying the Ride of Serendipity Dec 12, 2016

- Dec 6, 2016 Agnes Martin: A Singular Career Dec 6, 2016

Back to the Garden - Part 3: "You're a Good Egg—Happy Easter"

This is the third in a four-part series of posts based on an interview I conducted with the poet Hazel White, about the twenty-year process of writing her book Vigilance Is No Orchard, forthcoming from Nightboat Books. Scroll down for Parts 1 and 2.

Put the Relationship on the Page

In 2005, at California College of the Arts, the main feedback on my attempts to write about Isabelle and the garden was that my text lacked any sense of our relationship. I showed ten pages to the poet Leslie Scalapino. She hated it and spent an hour telling me in detail what was wrong with it. I agreed.

I joined a writing group and everyone said, We think you should put your relationship with Isabelle on the page.

Years later, when I had 60 pages written, I worked with the poet Rusty Morrison privately for a few sessions. She had a lot of critique. The title had the word shelter in it, but she wasn’t buying that the book was really about shelter. She thought that that word, that concept, was a safe placeholder. She said something about how the image of the garden “owned me and disowned me.” She encouraged me to take more risks with the whole manuscript.

I had thought it was almost done, so I was a bit shocked. And scared about taking those risks. I went to England. After a few months I gathered up the courage to read through all of Rusty’s written comments. Her observations felt completely right. But what she was suggesting—writing about what wasn’t sheltering me, of being lost over and over again in that image—seemed impossible. I realized that right from the beginning I’d clung to the topic of shelter because it was something I felt confident about and comfortable with. Rusty said, Take it out.

I needed to let everything go and write the messiness, make myself more lost!

I produced another version. I put everything I had into it. I met with Rusty again and this time she seemed to think I’d succeeded, or done well enough.

So I sent it out to poetry competitions. It was a finalist for both the Fence Books Ottoline Prize, chosen by Brenda Hillman, and the National Poetry Series. It seemed only a matter of time, I prayed, before it would be picked up by a publisher. I hoped I was done.

You’re a Good Egg—Happy Easter

Feeling more confident than I had in years, I sent the manuscript to Nightboat Books. The publisher, Stephen Motika, read it and said, I’m interested in your relationship with Isabelle and I don’t see it on the page.

I honestly didn’t think I could do anything more about it. I came to a grinding halt.

One day several months into my despair, I felt a different kind of energy—a little cocky, a little devil-may-care. I walked to the filing cabinet and took out a file overflowing with correspondence from Isabelle to me. Birthday cards, holiday cards, notes I had saved. With a kind of weird, wild boldness I thought, I’ll give them this relationship. Flipping through the file I started writing things like, “You’re a Good Egg—Happy Easter.”

I should mention that during these years I’d become a close friend of Isabelle’s, in spite of the fact that I’d failed to publish a book about her and the garden I was so obsessed with. She’d gotten married—in that same garden. I’d attended the wedding, even helped her dress for the ceremony. In my maniacal writing fit, I included details about how I helped her that day with her corset and shoes. I produced about eight pages of quotes and inserted them into the manuscript.

I sent it off to Stephen. I was just waiting for him to reject it.

Next Installment: Mountain Lion Footprints on the Deck

-

August 2021

- Aug 31, 2021 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 9: The Teacher Role Isn't My Essence Aug 31, 2021

-

June 2021

- Jun 13, 2021 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 8: Machines Spilling Out Teachers Jun 13, 2021

-

April 2021

- Apr 14, 2021 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 7: A Waterfall of Inspiration Apr 14, 2021

-

February 2021

- Feb 14, 2021 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 6: Grab the Right Computer File Feb 14, 2021

-

December 2020

- Dec 26, 2020 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 5: Yoga Is My Second Child Dec 26, 2020

-

November 2020

- Nov 5, 2020 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 4: Wow, This Is Me Nov 5, 2020

-

October 2020

- Oct 4, 2020 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 3: In Exile in My Own Country Oct 4, 2020

-

August 2020

- Aug 23, 2020 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 2: Openness to the Unseen Aug 23, 2020

- Aug 2, 2020 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 1: Let's Move Around; We'll Feel Better Aug 2, 2020

-

July 2020

- Jul 25, 2020 Educator Wellness Series Conclusion: Moving Forward with Wellness Jul 25, 2020

- Jul 6, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #10: Inhabiting the Dignified Stance of "Adequate" Jul 6, 2020

-

June 2020

- Jun 17, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #9: Jun 17, 2020

- Jun 3, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #8: Reducing Stress Through Body Scanning Jun 3, 2020

-

May 2020

- May 21, 2020 Facebook Live Event: A Conversation About the Impact of Saying Goodbye to Students May 21, 2020

- May 13, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #7: Setting Intention and Letting Go of Results May 13, 2020

- May 6, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #6: Practicing Goodwill as Self-Care May 6, 2020

-

April 2020

- Apr 29, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #5: Dealing with Constant Change Apr 29, 2020

- Apr 22, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #4: Listening to Silence Apr 22, 2020

- Apr 21, 2020 Facebook Live Event: A Conversation About the Importance of Self-Care Apr 21, 2020

- Apr 15, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #3: Apr 15, 2020

- Apr 8, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #2: Engaging Wisely with News and Media Apr 8, 2020

- Apr 1, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #1: Breathe ... Keep Breathing Apr 1, 2020

-

March 2020

- Mar 25, 2020 Educator Wellness Series for Collaborative Classroom Mar 25, 2020

-

May 2019

- May 19, 2019 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 8: Do We Want to Be Right in a Dictionary Sense? May 19, 2019

-

April 2019

- Apr 27, 2019 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 7: You Just Need to Find a Good Husband Apr 27, 2019

- Apr 6, 2019 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 6: Human Remains and Cultural Artifacts Apr 6, 2019

-

March 2019

- Mar 17, 2019 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 5: Poetry Has No Rules Mar 17, 2019

- Mar 3, 2019 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 4: Dessert Goes to a Different Stomach Mar 3, 2019

-

January 2019

- Jan 13, 2019 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 3: I Felt Pretty Stupid Jan 13, 2019

-

December 2018

- Dec 9, 2018 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 2: Such a Bad Kid Dec 9, 2018

-

November 2018

- Nov 23, 2018 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 1: The Pressure to Be a Certain Type of Girl Nov 23, 2018

-

October 2018

- Oct 23, 2018 Leadership Without Ego - Part 6: Mayberry with an Edge Oct 23, 2018

- Oct 1, 2018 Leadership Without Ego - Part 5: Everyone Everywhere Deserves to Make Art Oct 1, 2018

-

September 2018

- Sep 10, 2018 Leadership Without Ego - Part 4: I'm About Ready to Swear Sep 10, 2018

-

August 2018

- Aug 19, 2018 Leadership Without Ego - Part 3: The Dalai Lama Breaks All the Rules Aug 19, 2018

-

July 2018

- Jul 29, 2018 Leadership Without Ego - Part 2: The Kids Melted Under That Praise Jul 29, 2018

- Jul 10, 2018 Leadership Without Ego - Part 1: The Workshop Was Neutral Territory Jul 10, 2018

-

May 2018

- May 26, 2018 The Alchemy of Service - Part 5: Watch Out, Someone's Behind You May 26, 2018

- May 6, 2018 The Alchemy of Service - Part 4: Fireworks and Tears May 6, 2018

- May 5, 2018 The Alchemy of Service - Part 3: Joann Wong! You Are Chinese! May 5, 2018

-

April 2018

- Apr 6, 2018 The Alchemy of Service - Part 2: Mom, It's Only a Nickel Apr 6, 2018

-

March 2018

- Mar 19, 2018 The Alchemy of Service - Part 1: Mouse Soup Mar 19, 2018

-

February 2018

- Feb 18, 2018 Back to the Garden - Part 4: Mountain Lion Footprints on the Deck Feb 18, 2018

- Feb 3, 2018 Back to the Garden - Part 3: "You're a Good Egg—Happy Easter" Feb 3, 2018

-

January 2018

- Jan 15, 2018 Back to the Garden - Part 2: "A Pretty Big Failure" Jan 15, 2018

- Jan 1, 2018 Back to the Garden - Part 1: "Aesthetic Shock" Jan 1, 2018

-

August 2017

- Aug 15, 2017 Goodbye Self-esteem, Hello Self-compassion – Part 3: Real Love Aug 15, 2017

-

July 2017

- Jul 31, 2017 Goodbye Self-esteem, Hello Self-compassion – Part 2: Mirror, Mirror Jul 31, 2017

- Jul 17, 2017 Goodbye Self-esteem, Hello Self-compassion – Part 1: Bashing Vasco Jul 17, 2017

-

May 2017

- May 28, 2017 This Thing I Found: Teens Teach Us How to See Freshly May 28, 2017

-

March 2017

- Mar 20, 2017 Dream On - Part 6: Dream Analysis Example Mar 20, 2017

- Mar 7, 2017 Dream On - Part 5: A Dream Analysis Technique (cont.) Mar 7, 2017

-

February 2017

- Feb 20, 2017 Dream On - Part 4: A Dream Analysis Technique Feb 20, 2017

-

January 2017

- Jan 22, 2017 Dream On - Part 3: Recording Dreams Jan 22, 2017

- Jan 15, 2017 Dream On - Part 2: Dream Recall Jan 15, 2017

-

December 2016

- Dec 30, 2016 Dream On – Part 1 Dec 30, 2016

- Dec 12, 2016 Enjoying the Ride of Serendipity Dec 12, 2016

- Dec 6, 2016 Agnes Martin: A Singular Career Dec 6, 2016

Back to the Garden - Part 2: "A Pretty Big Failure"

This is the second in a four-part series of posts based on an interview I conducted with the poet Hazel White, about the twenty-year process of writing her book Vigilance Is No Orchard, forthcoming from Nightboat Books. Scroll down for Part 1.

A Pretty Big Failure

Isabelle had a show at the UC Santa Barbara Art Museum. I wrote a catalog essay for it. A publisher of some note came to the show, became wildly interested in her work, and wanted to publish a series of books on her. Later, I had a verbal contract with the publisher to write one of the books, but due to an economic downturn in publishing, the project fell through.

Hazel with Isabelle Greene

Exhibit catalog for Isabelle's show at the UC Santa Barbara Art Museum

At another point, my partner agreed I could take a year off from earning income to write a book about Isabelle. At the end of the year, with nothing much written and feeling miserable, I got brave and contacted the top agent for landscape books in New York—office on 5th Avenue, the works. She was interested but thought Isabelle wasn’t sufficiently well known to warrant an entire book just about her. The agent wanted me to write a book about Isabelle and another landscape architect. I turned her down; it didn’t feel possible to compromise. I’m sure she was very surprised.

Then I decided that in order to write the book I needed to attend a Master of Fine Arts writing program. I got into the MFA program at California College of the Arts. At the end of the first semester, a professor told me that she didn’t think I could write the book about Isabelle’s garden for probably five years. I went home and cried.

By the second semester, my writing had broken down completely. I could no longer write a linear sentence. Friends were telling me I should drop the book idea. It was looking like a pretty big failure. I suppose the breakdown in sentences was related to my emotional state. Something had to break.

At that point I took a course called “Hybrid Forms” taught by the poet Kathleen Fraser. Being a good girl and following her directions, I produced these short condensed pieces in response to her exercise prompts. She called them poems. I was terrified—I didn’t want them to be called poems. I couldn’t face my inability to write sentences anymore. I made a valiant attempt to get the hell out of this huge discomfort and transfer to the Visual and Critical Studies program, but wasn’t able to.

I had grown up in a working-class family. I’d argued my way to college based on the expectation that I’d make money. So writing poetry felt like a crisis. Yet I could no longer write anything else.

Hazel as a child (Hazel's on the right)

Hazel as a teen, on a farm in the southwest of England, where she grew up

A couple years after receiving my MFA, I wrote my first poetry book, Peril as Architectural Enrichment, in the space of about four months. It was published by Kelsey Street Press in 2011. It dealt with landscape architecture—but wasn’t about Isabelle and her garden. I felt guilty. I had accrued 70 hours of interviews with Isabelle yet I had been unable to produce anything out of all that material.

Next Installment: You're a Good Egg—Happy Easter

-

August 2021

- Aug 31, 2021 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 9: The Teacher Role Isn't My Essence Aug 31, 2021

-

June 2021

- Jun 13, 2021 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 8: Machines Spilling Out Teachers Jun 13, 2021

-

April 2021

- Apr 14, 2021 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 7: A Waterfall of Inspiration Apr 14, 2021

-

February 2021

- Feb 14, 2021 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 6: Grab the Right Computer File Feb 14, 2021

-

December 2020

- Dec 26, 2020 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 5: Yoga Is My Second Child Dec 26, 2020

-

November 2020

- Nov 5, 2020 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 4: Wow, This Is Me Nov 5, 2020

-

October 2020

- Oct 4, 2020 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 3: In Exile in My Own Country Oct 4, 2020

-

August 2020

- Aug 23, 2020 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 2: Openness to the Unseen Aug 23, 2020

- Aug 2, 2020 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 1: Let's Move Around; We'll Feel Better Aug 2, 2020

-

July 2020

- Jul 25, 2020 Educator Wellness Series Conclusion: Moving Forward with Wellness Jul 25, 2020

- Jul 6, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #10: Inhabiting the Dignified Stance of "Adequate" Jul 6, 2020

-

June 2020

- Jun 17, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #9: Jun 17, 2020

- Jun 3, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #8: Reducing Stress Through Body Scanning Jun 3, 2020

-

May 2020

- May 21, 2020 Facebook Live Event: A Conversation About the Impact of Saying Goodbye to Students May 21, 2020

- May 13, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #7: Setting Intention and Letting Go of Results May 13, 2020

- May 6, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #6: Practicing Goodwill as Self-Care May 6, 2020

-

April 2020

- Apr 29, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #5: Dealing with Constant Change Apr 29, 2020

- Apr 22, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #4: Listening to Silence Apr 22, 2020

- Apr 21, 2020 Facebook Live Event: A Conversation About the Importance of Self-Care Apr 21, 2020

- Apr 15, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #3: Apr 15, 2020

- Apr 8, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #2: Engaging Wisely with News and Media Apr 8, 2020

- Apr 1, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #1: Breathe ... Keep Breathing Apr 1, 2020

-

March 2020

- Mar 25, 2020 Educator Wellness Series for Collaborative Classroom Mar 25, 2020

-

May 2019

- May 19, 2019 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 8: Do We Want to Be Right in a Dictionary Sense? May 19, 2019

-

April 2019

- Apr 27, 2019 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 7: You Just Need to Find a Good Husband Apr 27, 2019

- Apr 6, 2019 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 6: Human Remains and Cultural Artifacts Apr 6, 2019

-

March 2019

- Mar 17, 2019 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 5: Poetry Has No Rules Mar 17, 2019

- Mar 3, 2019 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 4: Dessert Goes to a Different Stomach Mar 3, 2019

-

January 2019

- Jan 13, 2019 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 3: I Felt Pretty Stupid Jan 13, 2019

-

December 2018

- Dec 9, 2018 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 2: Such a Bad Kid Dec 9, 2018

-

November 2018

- Nov 23, 2018 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 1: The Pressure to Be a Certain Type of Girl Nov 23, 2018

-

October 2018

- Oct 23, 2018 Leadership Without Ego - Part 6: Mayberry with an Edge Oct 23, 2018

- Oct 1, 2018 Leadership Without Ego - Part 5: Everyone Everywhere Deserves to Make Art Oct 1, 2018

-

September 2018

- Sep 10, 2018 Leadership Without Ego - Part 4: I'm About Ready to Swear Sep 10, 2018

-

August 2018

- Aug 19, 2018 Leadership Without Ego - Part 3: The Dalai Lama Breaks All the Rules Aug 19, 2018

-

July 2018

- Jul 29, 2018 Leadership Without Ego - Part 2: The Kids Melted Under That Praise Jul 29, 2018

- Jul 10, 2018 Leadership Without Ego - Part 1: The Workshop Was Neutral Territory Jul 10, 2018

-

May 2018

- May 26, 2018 The Alchemy of Service - Part 5: Watch Out, Someone's Behind You May 26, 2018

- May 6, 2018 The Alchemy of Service - Part 4: Fireworks and Tears May 6, 2018

- May 5, 2018 The Alchemy of Service - Part 3: Joann Wong! You Are Chinese! May 5, 2018

-

April 2018

- Apr 6, 2018 The Alchemy of Service - Part 2: Mom, It's Only a Nickel Apr 6, 2018

-

March 2018

- Mar 19, 2018 The Alchemy of Service - Part 1: Mouse Soup Mar 19, 2018

-

February 2018

- Feb 18, 2018 Back to the Garden - Part 4: Mountain Lion Footprints on the Deck Feb 18, 2018

- Feb 3, 2018 Back to the Garden - Part 3: "You're a Good Egg—Happy Easter" Feb 3, 2018

-

January 2018

- Jan 15, 2018 Back to the Garden - Part 2: "A Pretty Big Failure" Jan 15, 2018

- Jan 1, 2018 Back to the Garden - Part 1: "Aesthetic Shock" Jan 1, 2018

-

August 2017

- Aug 15, 2017 Goodbye Self-esteem, Hello Self-compassion – Part 3: Real Love Aug 15, 2017

-

July 2017

- Jul 31, 2017 Goodbye Self-esteem, Hello Self-compassion – Part 2: Mirror, Mirror Jul 31, 2017

- Jul 17, 2017 Goodbye Self-esteem, Hello Self-compassion – Part 1: Bashing Vasco Jul 17, 2017

-

May 2017

- May 28, 2017 This Thing I Found: Teens Teach Us How to See Freshly May 28, 2017

-

March 2017

- Mar 20, 2017 Dream On - Part 6: Dream Analysis Example Mar 20, 2017

- Mar 7, 2017 Dream On - Part 5: A Dream Analysis Technique (cont.) Mar 7, 2017

-

February 2017

- Feb 20, 2017 Dream On - Part 4: A Dream Analysis Technique Feb 20, 2017

-

January 2017

- Jan 22, 2017 Dream On - Part 3: Recording Dreams Jan 22, 2017

- Jan 15, 2017 Dream On - Part 2: Dream Recall Jan 15, 2017

-

December 2016

- Dec 30, 2016 Dream On – Part 1 Dec 30, 2016

- Dec 12, 2016 Enjoying the Ride of Serendipity Dec 12, 2016

- Dec 6, 2016 Agnes Martin: A Singular Career Dec 6, 2016

Back to the Garden - Part 1: "Aesthetic Shock"

This is the first in a four-part series of posts based on an interview I conducted with the poet Hazel White, about the twenty-year process of writing her book Vigilance Is No Orchard, forthcoming from Nightboat Books. It’s a story of intense commitment to carrying out a creative vision no matter how challenging the process.

Aesthetic Shock

I started out as a freelance writer, writing primarily about landscape architecture and gardening. I have loved poetry since childhood, but I always had this thought running through my head: “Poetry is the hardest thing in the world; I’m going nowhere near it.”

One day twenty years ago, I turned a page in a magazine and saw a photograph of an amazing garden. It was an aesthetic shock. I felt physically jolted. I knew instantaneously that I would do whatever was required to stand in that garden.

I had long believed that our most essential experience of place or space is about shelter and view. Now I think the maker of the garden, landscape architect Isabelle Greene, had triggered my almost paranormal experience through an exquisite manipulation of those two elements. The garden sits in a tight canyon; a series of freeform terraces step down the hill.

I thought that if I could just stand in that garden, I would understand it.

The Valentine Garden, designed by landscape architect Isabelle Greene

Within 24 hours I’d called Isabelle Greene at her Santa Barbara office. Too shy to say, “I’ve had an aesthetic shock,” I presented myself as a garden writer and explained that I was writing books for Chronicle Books on garden design and used that as an excuse to ask if I could come see her work.

She asked why I was writing gardening books. I said I wanted to teach ordinary gardeners what professional landscape architects know about space. I’d taken a lot of landscape architecture classes at UC Berkeley Extension and had read a lot about the philosophy of space. She said she didn’t think this was something that could be taught. And she wasn’t compelled enough by my story to meet me or let me see the famous garden she had made for Carol Valentine, in Montecito.

Years later, when I told her the truth, she said, My god, if you’d just said so, I would have gotten you into that garden immediately. So I had shot myself in the foot by not being honest.

Access to the Garden

Each year for the next four years, while I was writing other books in the Chronicle garden design series, I called her assistant and asked if I could come down and see some gardens and maybe meet with Isabelle. I was always told, “She’s busy, but you’re welcome to come see some of her work.”

In Year Four, I called the assistant as usual. This time I suggested that if Isabelle had a favorite restaurant, I’d be happy to take her to dinner. That approach broke through! I went down there and we met for dinner. Within five minutes we were talking about line and form and whose work we loved. It was immediately obvious that we were both crazy about landscape.

Hazel White

She explained to me that the inspiration for the Valentine garden—her most famous creation—came from aerial views of the California landscape. She was particularly interested in the straight lines of fields and how they get interrupted by a creek or a river or foothills. She was interested in that meeting of a strong, human-made line against a natural line. The garden photograph I’d seen had the most extraordinary resonance with aerial photos of landscapes. But in the view in the photograph, you’re actually only looking down thirty feet. Isabelle had manipulated the scale such that the viewer sees terraces that are large in themselves, but are a miniaturization of the much larger landscape you’d see from a plane.

She finally arranged for me to see the garden.

All those years, I had been confident that once I was standing there I would know the particular power of that garden. I thought back then that I could pretty much understand and write about any landscape architecture using a set of concepts I’d become familiar with. I had been quite successful doing so, getting my work published in the London Telegraph Sunday magazine and so on.

Standing in the garden, I felt a strange alertness, a fizziness in my nervous system—yet I couldn’t figure out what was producing the effect. It would be a long time before I was capable of writing anything sufficient about this garden.

Next installment: "A Pretty Big Failure"

-

August 2021

- Aug 31, 2021 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 9: The Teacher Role Isn't My Essence Aug 31, 2021

-

June 2021

- Jun 13, 2021 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 8: Machines Spilling Out Teachers Jun 13, 2021

-

April 2021

- Apr 14, 2021 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 7: A Waterfall of Inspiration Apr 14, 2021

-

February 2021

- Feb 14, 2021 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 6: Grab the Right Computer File Feb 14, 2021

-

December 2020

- Dec 26, 2020 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 5: Yoga Is My Second Child Dec 26, 2020

-

November 2020

- Nov 5, 2020 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 4: Wow, This Is Me Nov 5, 2020

-

October 2020

- Oct 4, 2020 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 3: In Exile in My Own Country Oct 4, 2020

-

August 2020

- Aug 23, 2020 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 2: Openness to the Unseen Aug 23, 2020

- Aug 2, 2020 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 1: Let's Move Around; We'll Feel Better Aug 2, 2020

-

July 2020

- Jul 25, 2020 Educator Wellness Series Conclusion: Moving Forward with Wellness Jul 25, 2020

- Jul 6, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #10: Inhabiting the Dignified Stance of "Adequate" Jul 6, 2020

-

June 2020

- Jun 17, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #9: Jun 17, 2020

- Jun 3, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #8: Reducing Stress Through Body Scanning Jun 3, 2020

-

May 2020

- May 21, 2020 Facebook Live Event: A Conversation About the Impact of Saying Goodbye to Students May 21, 2020

- May 13, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #7: Setting Intention and Letting Go of Results May 13, 2020

- May 6, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #6: Practicing Goodwill as Self-Care May 6, 2020

-

April 2020

- Apr 29, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #5: Dealing with Constant Change Apr 29, 2020

- Apr 22, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #4: Listening to Silence Apr 22, 2020

- Apr 21, 2020 Facebook Live Event: A Conversation About the Importance of Self-Care Apr 21, 2020

- Apr 15, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #3: Apr 15, 2020

- Apr 8, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #2: Engaging Wisely with News and Media Apr 8, 2020

- Apr 1, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #1: Breathe ... Keep Breathing Apr 1, 2020

-

March 2020

- Mar 25, 2020 Educator Wellness Series for Collaborative Classroom Mar 25, 2020

-

May 2019

- May 19, 2019 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 8: Do We Want to Be Right in a Dictionary Sense? May 19, 2019

-

April 2019

- Apr 27, 2019 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 7: You Just Need to Find a Good Husband Apr 27, 2019

- Apr 6, 2019 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 6: Human Remains and Cultural Artifacts Apr 6, 2019

-

March 2019

- Mar 17, 2019 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 5: Poetry Has No Rules Mar 17, 2019

- Mar 3, 2019 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 4: Dessert Goes to a Different Stomach Mar 3, 2019

-

January 2019

- Jan 13, 2019 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 3: I Felt Pretty Stupid Jan 13, 2019

-

December 2018

- Dec 9, 2018 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 2: Such a Bad Kid Dec 9, 2018

-

November 2018

- Nov 23, 2018 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 1: The Pressure to Be a Certain Type of Girl Nov 23, 2018

-

October 2018

- Oct 23, 2018 Leadership Without Ego - Part 6: Mayberry with an Edge Oct 23, 2018

- Oct 1, 2018 Leadership Without Ego - Part 5: Everyone Everywhere Deserves to Make Art Oct 1, 2018

-

September 2018

- Sep 10, 2018 Leadership Without Ego - Part 4: I'm About Ready to Swear Sep 10, 2018

-

August 2018

- Aug 19, 2018 Leadership Without Ego - Part 3: The Dalai Lama Breaks All the Rules Aug 19, 2018

-

July 2018

- Jul 29, 2018 Leadership Without Ego - Part 2: The Kids Melted Under That Praise Jul 29, 2018

- Jul 10, 2018 Leadership Without Ego - Part 1: The Workshop Was Neutral Territory Jul 10, 2018

-

May 2018

- May 26, 2018 The Alchemy of Service - Part 5: Watch Out, Someone's Behind You May 26, 2018

- May 6, 2018 The Alchemy of Service - Part 4: Fireworks and Tears May 6, 2018

- May 5, 2018 The Alchemy of Service - Part 3: Joann Wong! You Are Chinese! May 5, 2018

-

April 2018

- Apr 6, 2018 The Alchemy of Service - Part 2: Mom, It's Only a Nickel Apr 6, 2018

-

March 2018

- Mar 19, 2018 The Alchemy of Service - Part 1: Mouse Soup Mar 19, 2018

-

February 2018

- Feb 18, 2018 Back to the Garden - Part 4: Mountain Lion Footprints on the Deck Feb 18, 2018

- Feb 3, 2018 Back to the Garden - Part 3: "You're a Good Egg—Happy Easter" Feb 3, 2018

-

January 2018

- Jan 15, 2018 Back to the Garden - Part 2: "A Pretty Big Failure" Jan 15, 2018

- Jan 1, 2018 Back to the Garden - Part 1: "Aesthetic Shock" Jan 1, 2018

-

August 2017

- Aug 15, 2017 Goodbye Self-esteem, Hello Self-compassion – Part 3: Real Love Aug 15, 2017

-

July 2017

- Jul 31, 2017 Goodbye Self-esteem, Hello Self-compassion – Part 2: Mirror, Mirror Jul 31, 2017

- Jul 17, 2017 Goodbye Self-esteem, Hello Self-compassion – Part 1: Bashing Vasco Jul 17, 2017

-

May 2017

- May 28, 2017 This Thing I Found: Teens Teach Us How to See Freshly May 28, 2017

-

March 2017

- Mar 20, 2017 Dream On - Part 6: Dream Analysis Example Mar 20, 2017

- Mar 7, 2017 Dream On - Part 5: A Dream Analysis Technique (cont.) Mar 7, 2017

-

February 2017

- Feb 20, 2017 Dream On - Part 4: A Dream Analysis Technique Feb 20, 2017

-

January 2017

- Jan 22, 2017 Dream On - Part 3: Recording Dreams Jan 22, 2017

- Jan 15, 2017 Dream On - Part 2: Dream Recall Jan 15, 2017

-

December 2016

- Dec 30, 2016 Dream On – Part 1 Dec 30, 2016

- Dec 12, 2016 Enjoying the Ride of Serendipity Dec 12, 2016

- Dec 6, 2016 Agnes Martin: A Singular Career Dec 6, 2016

This Thing I Found: Teens Teach Us How to See Freshly

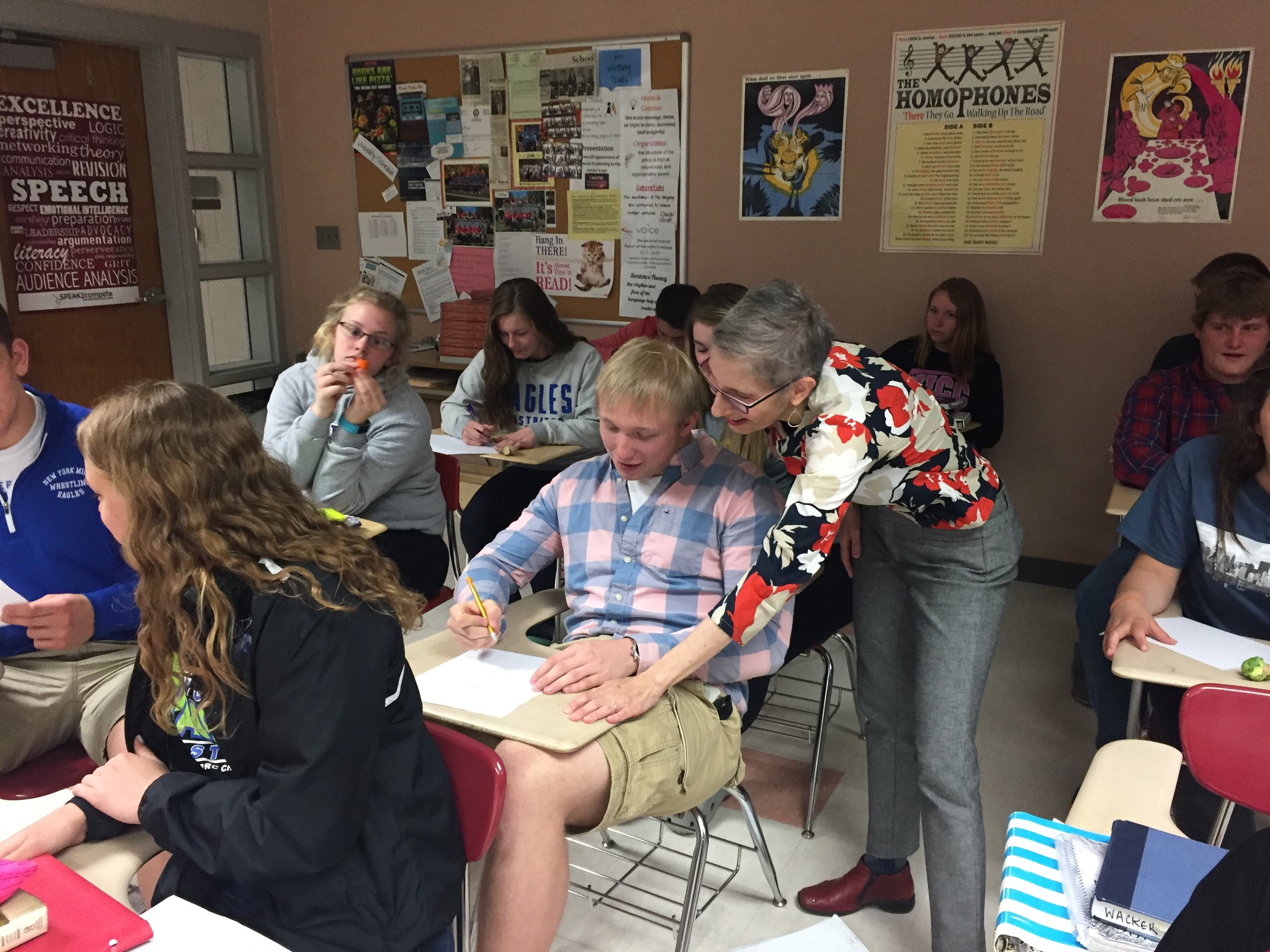

Recently I returned to an earlier incarnation, teaching a couple poetry classes at the high school in New York Mills, a town in upstate Minnesota where I've just completed a writing residency. I taught poetry pretty intensively for a number of years but that was a while ago. I loved re-entering “the classroom.” (As if it’s the same classroom, wherever one is—and that’s true, in a certain way—and not, in others. But I digress.).

Kasey Wacker, the teacher, had informed me that her 11th graders had all written poems, but not many, and not in quite a while. I chose a lesson built around an excerpt from Wallace Stevens’ poem “Someone Puts a Pineapple Together.”

Like his “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird,” each line in this poem asks the reader to look at a pineapple in an entirely new way. The second stanza, for example, reads:

4. The sea is sprouting upward out of rocks.

5. The symbol of feasts and of oblivion . . .

6. White sky, pink sun, trees on a distant peak.

As I held a pineapple aloft, we discussed Stevens’ strategies for waking up our powers of perception. Not only does Stevens give us a new image in each numbered line; he also changes up the syntax (a whole sentence followed by two fragments), the use of punctuation, the music of the language, the scale (from a rock to a mountain), and the type of figurative language employed (metaphoric in lines 4 and 6; symbolism in line 5). The vocabulary too is full of surprises, like the word “sprouting” where you’d expect “spouting”—so you get the spouting action of water but also the sense that the water is alive, growing up out of the rocks.

And that’s just one stanza!

I then gave the students each their own fruit or vegetable and asked them to employ some of Stevens’ strategies to write their own poems. With remarkably little experience in the genre, they dove right in.

My coachy takeaway? Find some teenagers to hang around with. They are coming into their full power as interesting individuals with big brains. Yet their curiosity and permeability can remind us older humans to break out of our ruts and responsibilities, give ourselves fully to life, receiving life’s goodies in return.

Kasey sent me all 40 poems afterward. Part of me wants to publish all 40. Instead, I'll tantalize you with a smattering of the great work Kasey's students did (see below). Even in this sample there's a range of forms and tones—enjoy!

What (brussels sprout)

Round like a watermelon, yet small.

The fresh smell, a Sunday morning in May.

Each layer barely over the next.

Like the veins in a heart.

They go towards the center.

The whole is nothing without the center.

The center is irrelevant without the whole.

Each layer a limb, each piece a muscle.

With more power in than out, the body develops.

One day it stops, and the Sunday morning turns to Monday. —Jake

This Thing I Found (brussels sprout)

Green and round,

this thing I found.

With veiny leaves,

and no fleas. —Maddie

The Things You Can See (small yellow pepper)

1. The bulb hung alone on the tree.

2. The tiny pot held the most beautiful upside down flower.

3. Would they ever pull the sword out of the stone?

4. Can you hear that bell . . .

5. Look! That bird has no legs.

6. The mushroom was covered in bumps. —Kaitlyn Dykhoff

A Cherry Pulled Apart (ground cherry)

1. The dark green rivers within

2. The tail of the taut mouse slips away

3. An egg inside a frail shell

4. Wrinkling away as new arrives within

5. The brightness within the dark

6. Veins of the animal show through battered skin

7. A hut of darkness with life within

8. The old man hardened with kindness in his soul

Poem (reaper pepper)

The wrinkled red reaper is as hot as the summer

days gives you chills like the winter nights.

Red as blood, vivid as a memory, exotic as a bird.

Its thin hide reveals the tasty beauty inside.

At Peace (potato)

The bird, plump and bald

perches; bathing in the light,

in a deep slumber.

The Hand (ginger)

1 From the swallows of the tomb

2 came the hand

3 crawling creepily, steadily

4 it emerged

5 into the dawn, the light

6 it wrinkled, decaying

7 twisted, crisped, squirming

8 dying in the rays

9 from the bitter son

10 so back to the swallows

11 it retreated

12 sobbing, anguished, lifeless

13 gone

-

December 2016

- Dec 6, 2016 Agnes Martin: A Singular Career Dec 6, 2016

- Dec 12, 2016 Enjoying the Ride of Serendipity Dec 12, 2016

- Dec 30, 2016 Dream On – Part 1 Dec 30, 2016

-

January 2017

- Jan 15, 2017 Dream On - Part 2: Dream Recall Jan 15, 2017

- Jan 22, 2017 Dream On - Part 3: Recording Dreams Jan 22, 2017

-

February 2017

- Feb 20, 2017 Dream On - Part 4: A Dream Analysis Technique Feb 20, 2017

-

March 2017

- Mar 7, 2017 Dream On - Part 5: A Dream Analysis Technique (cont.) Mar 7, 2017

- Mar 20, 2017 Dream On - Part 6: Dream Analysis Example Mar 20, 2017

-

May 2017

- May 28, 2017 This Thing I Found: Teens Teach Us How to See Freshly May 28, 2017

-

July 2017

- Jul 17, 2017 Goodbye Self-esteem, Hello Self-compassion – Part 1: Bashing Vasco Jul 17, 2017

- Jul 31, 2017 Goodbye Self-esteem, Hello Self-compassion – Part 2: Mirror, Mirror Jul 31, 2017

-

August 2017

- Aug 15, 2017 Goodbye Self-esteem, Hello Self-compassion – Part 3: Real Love Aug 15, 2017

-

January 2018

- Jan 1, 2018 Back to the Garden - Part 1: "Aesthetic Shock" Jan 1, 2018

- Jan 15, 2018 Back to the Garden - Part 2: "A Pretty Big Failure" Jan 15, 2018

-

February 2018

- Feb 3, 2018 Back to the Garden - Part 3: "You're a Good Egg—Happy Easter" Feb 3, 2018

- Feb 18, 2018 Back to the Garden - Part 4: Mountain Lion Footprints on the Deck Feb 18, 2018

-

March 2018

- Mar 19, 2018 The Alchemy of Service - Part 1: Mouse Soup Mar 19, 2018

-

April 2018

- Apr 6, 2018 The Alchemy of Service - Part 2: Mom, It's Only a Nickel Apr 6, 2018

-

May 2018

- May 5, 2018 The Alchemy of Service - Part 3: Joann Wong! You Are Chinese! May 5, 2018

- May 6, 2018 The Alchemy of Service - Part 4: Fireworks and Tears May 6, 2018

- May 26, 2018 The Alchemy of Service - Part 5: Watch Out, Someone's Behind You May 26, 2018

-

July 2018

- Jul 10, 2018 Leadership Without Ego - Part 1: The Workshop Was Neutral Territory Jul 10, 2018

- Jul 29, 2018 Leadership Without Ego - Part 2: The Kids Melted Under That Praise Jul 29, 2018

-

August 2018

- Aug 19, 2018 Leadership Without Ego - Part 3: The Dalai Lama Breaks All the Rules Aug 19, 2018

-

September 2018

- Sep 10, 2018 Leadership Without Ego - Part 4: I'm About Ready to Swear Sep 10, 2018

-

October 2018

- Oct 1, 2018 Leadership Without Ego - Part 5: Everyone Everywhere Deserves to Make Art Oct 1, 2018

- Oct 23, 2018 Leadership Without Ego - Part 6: Mayberry with an Edge Oct 23, 2018

-

November 2018

- Nov 23, 2018 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 1: The Pressure to Be a Certain Type of Girl Nov 23, 2018

-

December 2018

- Dec 9, 2018 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 2: Such a Bad Kid Dec 9, 2018

-

January 2019

- Jan 13, 2019 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 3: I Felt Pretty Stupid Jan 13, 2019

-

March 2019

- Mar 3, 2019 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 4: Dessert Goes to a Different Stomach Mar 3, 2019

- Mar 17, 2019 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 5: Poetry Has No Rules Mar 17, 2019

-

April 2019

- Apr 6, 2019 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 6: Human Remains and Cultural Artifacts Apr 6, 2019

- Apr 27, 2019 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 7: You Just Need to Find a Good Husband Apr 27, 2019

-

May 2019

- May 19, 2019 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 8: Do We Want to Be Right in a Dictionary Sense? May 19, 2019

-

March 2020

- Mar 25, 2020 Educator Wellness Series for Collaborative Classroom Mar 25, 2020

-

April 2020

- Apr 1, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #1: Breathe ... Keep Breathing Apr 1, 2020

- Apr 8, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #2: Engaging Wisely with News and Media Apr 8, 2020

- Apr 15, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #3: Apr 15, 2020

- Apr 21, 2020 Facebook Live Event: A Conversation About the Importance of Self-Care Apr 21, 2020

- Apr 22, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #4: Listening to Silence Apr 22, 2020

- Apr 29, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #5: Dealing with Constant Change Apr 29, 2020

-

May 2020

- May 6, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #6: Practicing Goodwill as Self-Care May 6, 2020

- May 13, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #7: Setting Intention and Letting Go of Results May 13, 2020

- May 21, 2020 Facebook Live Event: A Conversation About the Impact of Saying Goodbye to Students May 21, 2020

-

June 2020

- Jun 3, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #8: Reducing Stress Through Body Scanning Jun 3, 2020

- Jun 17, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #9: Jun 17, 2020

-

July 2020

- Jul 6, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #10: Inhabiting the Dignified Stance of "Adequate" Jul 6, 2020

- Jul 25, 2020 Educator Wellness Series Conclusion: Moving Forward with Wellness Jul 25, 2020

-

August 2020

- Aug 2, 2020 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 1: Let's Move Around; We'll Feel Better Aug 2, 2020

- Aug 23, 2020 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 2: Openness to the Unseen Aug 23, 2020

-

October 2020

- Oct 4, 2020 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 3: In Exile in My Own Country Oct 4, 2020

-

November 2020

- Nov 5, 2020 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 4: Wow, This Is Me Nov 5, 2020

-

December 2020

- Dec 26, 2020 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 5: Yoga Is My Second Child Dec 26, 2020

-

February 2021

- Feb 14, 2021 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 6: Grab the Right Computer File Feb 14, 2021

-

April 2021

- Apr 14, 2021 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 7: A Waterfall of Inspiration Apr 14, 2021

-

June 2021

- Jun 13, 2021 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 8: Machines Spilling Out Teachers Jun 13, 2021

-

August 2021

- Aug 31, 2021 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 9: The Teacher Role Isn't My Essence Aug 31, 2021

Dream On - Part 5: A Dream Analysis Technique (cont.)

Hey, dreamer, in my last post I addressed three of the six basic principles you need to grok dreams the Gestalt way:

- Everything in the dream is an aspect of the dreamer

- The dreamer reenacts the dream in the here-and-now

- The dreamer sticks to the scenario of the dream, instead of generalizing based on waking life

In this post we'll look at the remaining three principles :

- The parts that are not “I” are emerging consciousness

- Dreams are embodied consciousness

- Only the dreamer can discover the dream’s meaning

Zooming in a bit closer:

The parts that are not “I” are emerging consciousness: The elements of the dream that are not the “I” are seen in Gestalt theory as emerging consciousness—present but not quite ready to be “owned” by the dreamer. By inhabiting the point of view of each element in turn, the individual sees the dream scenario from new perspectives that often yield surprising insights. (Even elements that seem destructive or in some way unacceptable from the perspective of the “I” can have revelatory messages when inhabited in the retelling. A tornado might be seen as terrifying by the “I,” but when inhabited, can reveal excitement.) The dreamer becomes conscious of what is on the edge of consciousness—so this is a growth experience, custom-designed for this individual at this point in her development by her own deeper self. According to Kenneth Meyer,

The point of dream work is not necessarily to discover something totally new, but to sharpen the existential dilemmas we find ourselves in, to strip away the details and circumstances that mute the felt-sense of our situations.

Dreams are embodied consciousness: Gestalt theory views dreams as embodied consciousness. Our dreams aren’t abstract thoughts—they are bodily metaphors. A person might dream of swimming in a pool and finding all the water draining out, leaving him sitting alone at the bottom of the cold, empty pool; this might be pointing to the way he has felt “let down” by others in real life, and to a “sinking” feeling he felt when he realized he was being “let down.” Perhaps when this experience occurred in real life, he did not directly deal with it. His dream shows up to give him a chance to face this “unfinished business” (a term coined by Gestalt theorists).

Note that Gestalt theorists see metaphors not as the results of verbal thinking, but as the source of language. The dream comes first; then we describe it in language. This accords with the perspective of linguist George Lakoff and philosopher Mark Johnson in their book Metaphors We Live By:

Metaphor is for most people a device of the poetic imagination and the rhetorical flourish—a matter of extraordinary rather than ordinary language. Moreover, metaphor is typically viewed as characteristic of language alone, a matter of words rather than thought or action. For this reason, most people think they can get along perfectly well without metaphor. We have found, on the contrary, that metaphor is pervasive in everyday life, not just in language but in thought and action. Our ordinary conceptual system, in terms of which we both think and act, is fundamentally metaphorical in nature.

Only the dreamer can discover the dream’s meaning: Gestalt theorists believe that only the individual can discover the meaning of his or her dream. In a longer dream workshop we would extend this this to include a practice whereby an individual whose dream is up for discussion can decide whether or not to invite group members to offer observations using the sentence frame “If this were my dream.” This frame, along with other discussion guidelines, ensure safety by making it clear that the individual is the owner of the dream and its meaning, and keeps us from giving advice. However, for today, we will not offer our own observations of others’ dreams.

In my next post, I'll demonstrate Gestalt dream analysis using one of my own dreams.

-

August 2021

- Aug 31, 2021 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 9: The Teacher Role Isn't My Essence Aug 31, 2021

-

June 2021

- Jun 13, 2021 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 8: Machines Spilling Out Teachers Jun 13, 2021

-

April 2021

- Apr 14, 2021 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 7: A Waterfall of Inspiration Apr 14, 2021

-

February 2021

- Feb 14, 2021 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 6: Grab the Right Computer File Feb 14, 2021

-

December 2020

- Dec 26, 2020 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 5: Yoga Is My Second Child Dec 26, 2020

-

November 2020

- Nov 5, 2020 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 4: Wow, This Is Me Nov 5, 2020

-

October 2020

- Oct 4, 2020 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 3: In Exile in My Own Country Oct 4, 2020

-

August 2020

- Aug 23, 2020 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 2: Openness to the Unseen Aug 23, 2020

- Aug 2, 2020 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 1: Let's Move Around; We'll Feel Better Aug 2, 2020

-

July 2020

- Jul 25, 2020 Educator Wellness Series Conclusion: Moving Forward with Wellness Jul 25, 2020

- Jul 6, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #10: Inhabiting the Dignified Stance of "Adequate" Jul 6, 2020

-

June 2020

- Jun 17, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #9: Jun 17, 2020

- Jun 3, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #8: Reducing Stress Through Body Scanning Jun 3, 2020

-

May 2020

- May 21, 2020 Facebook Live Event: A Conversation About the Impact of Saying Goodbye to Students May 21, 2020

- May 13, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #7: Setting Intention and Letting Go of Results May 13, 2020

- May 6, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #6: Practicing Goodwill as Self-Care May 6, 2020

-

April 2020

- Apr 29, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #5: Dealing with Constant Change Apr 29, 2020

- Apr 22, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #4: Listening to Silence Apr 22, 2020

- Apr 21, 2020 Facebook Live Event: A Conversation About the Importance of Self-Care Apr 21, 2020

- Apr 15, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #3: Apr 15, 2020

- Apr 8, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #2: Engaging Wisely with News and Media Apr 8, 2020

- Apr 1, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #1: Breathe ... Keep Breathing Apr 1, 2020

-

March 2020

- Mar 25, 2020 Educator Wellness Series for Collaborative Classroom Mar 25, 2020

-

May 2019

- May 19, 2019 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 8: Do We Want to Be Right in a Dictionary Sense? May 19, 2019

-

April 2019

- Apr 27, 2019 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 7: You Just Need to Find a Good Husband Apr 27, 2019

- Apr 6, 2019 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 6: Human Remains and Cultural Artifacts Apr 6, 2019

-

March 2019

- Mar 17, 2019 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 5: Poetry Has No Rules Mar 17, 2019

- Mar 3, 2019 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 4: Dessert Goes to a Different Stomach Mar 3, 2019

-

January 2019

- Jan 13, 2019 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 3: I Felt Pretty Stupid Jan 13, 2019

-

December 2018

- Dec 9, 2018 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 2: Such a Bad Kid Dec 9, 2018

-

November 2018

- Nov 23, 2018 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 1: The Pressure to Be a Certain Type of Girl Nov 23, 2018

-

October 2018

- Oct 23, 2018 Leadership Without Ego - Part 6: Mayberry with an Edge Oct 23, 2018

- Oct 1, 2018 Leadership Without Ego - Part 5: Everyone Everywhere Deserves to Make Art Oct 1, 2018

-

September 2018

- Sep 10, 2018 Leadership Without Ego - Part 4: I'm About Ready to Swear Sep 10, 2018

-

August 2018

- Aug 19, 2018 Leadership Without Ego - Part 3: The Dalai Lama Breaks All the Rules Aug 19, 2018

-

July 2018

- Jul 29, 2018 Leadership Without Ego - Part 2: The Kids Melted Under That Praise Jul 29, 2018

- Jul 10, 2018 Leadership Without Ego - Part 1: The Workshop Was Neutral Territory Jul 10, 2018

-

May 2018

- May 26, 2018 The Alchemy of Service - Part 5: Watch Out, Someone's Behind You May 26, 2018

- May 6, 2018 The Alchemy of Service - Part 4: Fireworks and Tears May 6, 2018

- May 5, 2018 The Alchemy of Service - Part 3: Joann Wong! You Are Chinese! May 5, 2018

-

April 2018

- Apr 6, 2018 The Alchemy of Service - Part 2: Mom, It's Only a Nickel Apr 6, 2018

-

March 2018

- Mar 19, 2018 The Alchemy of Service - Part 1: Mouse Soup Mar 19, 2018

-

February 2018

- Feb 18, 2018 Back to the Garden - Part 4: Mountain Lion Footprints on the Deck Feb 18, 2018

- Feb 3, 2018 Back to the Garden - Part 3: "You're a Good Egg—Happy Easter" Feb 3, 2018

-

January 2018

- Jan 15, 2018 Back to the Garden - Part 2: "A Pretty Big Failure" Jan 15, 2018

- Jan 1, 2018 Back to the Garden - Part 1: "Aesthetic Shock" Jan 1, 2018

-

August 2017

- Aug 15, 2017 Goodbye Self-esteem, Hello Self-compassion – Part 3: Real Love Aug 15, 2017

-

July 2017

- Jul 31, 2017 Goodbye Self-esteem, Hello Self-compassion – Part 2: Mirror, Mirror Jul 31, 2017

- Jul 17, 2017 Goodbye Self-esteem, Hello Self-compassion – Part 1: Bashing Vasco Jul 17, 2017

-

May 2017

- May 28, 2017 This Thing I Found: Teens Teach Us How to See Freshly May 28, 2017

-

March 2017

- Mar 20, 2017 Dream On - Part 6: Dream Analysis Example Mar 20, 2017

- Mar 7, 2017 Dream On - Part 5: A Dream Analysis Technique (cont.) Mar 7, 2017

-

February 2017

- Feb 20, 2017 Dream On - Part 4: A Dream Analysis Technique Feb 20, 2017

-

January 2017

- Jan 22, 2017 Dream On - Part 3: Recording Dreams Jan 22, 2017

- Jan 15, 2017 Dream On - Part 2: Dream Recall Jan 15, 2017

-

December 2016

- Dec 30, 2016 Dream On – Part 1 Dec 30, 2016

- Dec 12, 2016 Enjoying the Ride of Serendipity Dec 12, 2016

- Dec 6, 2016 Agnes Martin: A Singular Career Dec 6, 2016

-

August 2021

- Aug 31, 2021 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 9: The Teacher Role Isn't My Essence Aug 31, 2021

-

June 2021

- Jun 13, 2021 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 8: Machines Spilling Out Teachers Jun 13, 2021

-

April 2021

- Apr 14, 2021 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 7: A Waterfall of Inspiration Apr 14, 2021

-

February 2021

- Feb 14, 2021 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 6: Grab the Right Computer File Feb 14, 2021

-

December 2020

- Dec 26, 2020 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 5: Yoga Is My Second Child Dec 26, 2020

-

November 2020

- Nov 5, 2020 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 4: Wow, This Is Me Nov 5, 2020

-

October 2020

- Oct 4, 2020 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 3: In Exile in My Own Country Oct 4, 2020

-

August 2020

- Aug 23, 2020 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 2: Openness to the Unseen Aug 23, 2020

- Aug 2, 2020 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 1: Let's Move Around; We'll Feel Better Aug 2, 2020

-

July 2020

- Jul 25, 2020 Educator Wellness Series Conclusion: Moving Forward with Wellness Jul 25, 2020

- Jul 6, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #10: Inhabiting the Dignified Stance of "Adequate" Jul 6, 2020

-

June 2020

- Jun 17, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #9: Jun 17, 2020

- Jun 3, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #8: Reducing Stress Through Body Scanning Jun 3, 2020

-

May 2020

- May 21, 2020 Facebook Live Event: A Conversation About the Impact of Saying Goodbye to Students May 21, 2020

- May 13, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #7: Setting Intention and Letting Go of Results May 13, 2020

- May 6, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #6: Practicing Goodwill as Self-Care May 6, 2020

-

April 2020

- Apr 29, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #5: Dealing with Constant Change Apr 29, 2020

- Apr 22, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #4: Listening to Silence Apr 22, 2020

- Apr 21, 2020 Facebook Live Event: A Conversation About the Importance of Self-Care Apr 21, 2020

- Apr 15, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #3: Apr 15, 2020

- Apr 8, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #2: Engaging Wisely with News and Media Apr 8, 2020

- Apr 1, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #1: Breathe ... Keep Breathing Apr 1, 2020

-

March 2020

- Mar 25, 2020 Educator Wellness Series for Collaborative Classroom Mar 25, 2020

-

May 2019

- May 19, 2019 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 8: Do We Want to Be Right in a Dictionary Sense? May 19, 2019

-

April 2019

- Apr 27, 2019 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 7: You Just Need to Find a Good Husband Apr 27, 2019

- Apr 6, 2019 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 6: Human Remains and Cultural Artifacts Apr 6, 2019

-

March 2019

- Mar 17, 2019 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 5: Poetry Has No Rules Mar 17, 2019

- Mar 3, 2019 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 4: Dessert Goes to a Different Stomach Mar 3, 2019

-

January 2019

- Jan 13, 2019 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 3: I Felt Pretty Stupid Jan 13, 2019

-

December 2018

- Dec 9, 2018 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 2: Such a Bad Kid Dec 9, 2018

-

November 2018

- Nov 23, 2018 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 1: The Pressure to Be a Certain Type of Girl Nov 23, 2018

-

October 2018

- Oct 23, 2018 Leadership Without Ego - Part 6: Mayberry with an Edge Oct 23, 2018

- Oct 1, 2018 Leadership Without Ego - Part 5: Everyone Everywhere Deserves to Make Art Oct 1, 2018

-

September 2018

- Sep 10, 2018 Leadership Without Ego - Part 4: I'm About Ready to Swear Sep 10, 2018

-

August 2018

- Aug 19, 2018 Leadership Without Ego - Part 3: The Dalai Lama Breaks All the Rules Aug 19, 2018

-

July 2018

- Jul 29, 2018 Leadership Without Ego - Part 2: The Kids Melted Under That Praise Jul 29, 2018

- Jul 10, 2018 Leadership Without Ego - Part 1: The Workshop Was Neutral Territory Jul 10, 2018

-

May 2018

- May 26, 2018 The Alchemy of Service - Part 5: Watch Out, Someone's Behind You May 26, 2018

- May 6, 2018 The Alchemy of Service - Part 4: Fireworks and Tears May 6, 2018

- May 5, 2018 The Alchemy of Service - Part 3: Joann Wong! You Are Chinese! May 5, 2018

-

April 2018

- Apr 6, 2018 The Alchemy of Service - Part 2: Mom, It's Only a Nickel Apr 6, 2018

-

March 2018

- Mar 19, 2018 The Alchemy of Service - Part 1: Mouse Soup Mar 19, 2018

-

February 2018

- Feb 18, 2018 Back to the Garden - Part 4: Mountain Lion Footprints on the Deck Feb 18, 2018

- Feb 3, 2018 Back to the Garden - Part 3: "You're a Good Egg—Happy Easter" Feb 3, 2018

-

January 2018

- Jan 15, 2018 Back to the Garden - Part 2: "A Pretty Big Failure" Jan 15, 2018

- Jan 1, 2018 Back to the Garden - Part 1: "Aesthetic Shock" Jan 1, 2018

-

August 2017

- Aug 15, 2017 Goodbye Self-esteem, Hello Self-compassion – Part 3: Real Love Aug 15, 2017

-

July 2017

- Jul 31, 2017 Goodbye Self-esteem, Hello Self-compassion – Part 2: Mirror, Mirror Jul 31, 2017

- Jul 17, 2017 Goodbye Self-esteem, Hello Self-compassion – Part 1: Bashing Vasco Jul 17, 2017

-

May 2017

- May 28, 2017 This Thing I Found: Teens Teach Us How to See Freshly May 28, 2017

-

March 2017

- Mar 20, 2017 Dream On - Part 6: Dream Analysis Example Mar 20, 2017

- Mar 7, 2017 Dream On - Part 5: A Dream Analysis Technique (cont.) Mar 7, 2017

-

February 2017

- Feb 20, 2017 Dream On - Part 4: A Dream Analysis Technique Feb 20, 2017

-

January 2017

- Jan 22, 2017 Dream On - Part 3: Recording Dreams Jan 22, 2017

- Jan 15, 2017 Dream On - Part 2: Dream Recall Jan 15, 2017

-

December 2016

- Dec 30, 2016 Dream On – Part 1 Dec 30, 2016

- Dec 12, 2016 Enjoying the Ride of Serendipity Dec 12, 2016

- Dec 6, 2016 Agnes Martin: A Singular Career Dec 6, 2016

Dream On - Part 4: A Dream Analysis Technique

Approaches to dream analysis abound, including Freudian, Jungian, shamanic, culture dreaming, and problem solving techniques. One method I’m especially fond of is Gestalt dream analysis.

Gestalt psychology was developed by Fritz Perls (1893–1970) and Laura Posner Perls (1905–1990) in reaction to traditional psychoanalysis.

Instead of focusing on past trauma, Gestalt focuses on the here and now. It uses experiential techniques, including dream work, to help individuals safely and directly confront and work through difficulties. In addition to Fritz and Laura Perls’ early studies with leading psychologists, theologians, philosophers, and developers of bodywork approaches such as Feldenkreis and Alexander technique, Laura Perls was a student of movement and dance and an accomplished pianist, and Fritz Perls had a strong background in theater. Their artistic training is easily evident in the approach they developed, and this is in turn helps make Gestalt dream work particularly well suited to developing our creativity.

Basic principles of this approach include:

- Everything in the dream is an aspect of the dreamer

- The dreamer reenacts the dream in the here-and-now

- The dreamer sticks to the scenario of the dream, instead of generalizing based on waking life

- The parts that are not “I” are emerging consciousness

- Dreams are embodied consciousness

- Only the dreamer can discover the dream’s meaning

Let’s take a closer look at the first three of these principles: